Africa presents both great opportunities and challenges for fertilizers and their producers. Agriculture accounts for 16% of Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) and is the major source of income for rural residents. Africa also has the highest area of uncultivated, arable land (202 million ha.), about 50% of the world’s total. The consumption of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) on the continent has almost doubled since 2006 to 17 kg/ha., but there remains tremendous upside. As a report by the African Plant Nutrition Institute (APNI) notes, if Nigerian maize farmers were to incorporate optimal applications per hectare, yields would increase dramatically, from an average of 2 t/ha. to over 7 t, greatly enhancing the nation’s ability to feed itself.

Yet most of Africa’s farmers cannot access affordable fertilizer due to a number of factors. The African Fertilizer and Agribusiness Partnership (AFAP), a non-governmental organisation, notes that “fertilizer consumption among smallholder farmers, who make up the majority of farmers in the region and farm most of the land, has grown in the past decade but it is still far below what is needed as farmers face numerous challenges that limit their effective fertilizer demand.” Those challenges include little or no experience with fertilizers, no information regarding the right types and rates of application for their soils, limited access to finance, fragmented markets, high prices and poor infrastructure. Still, initiatives are underway to develop indigenous sources and improve accessibility to fertilizer.

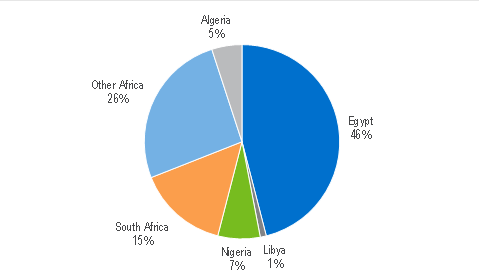

As Nexant, a San Francisco-based software, consulting, and services company, points out, „Africa has been blessed with many of the resources … [but] the trick for its fifty-plus governments will be to craft the right policies and incentives to make optimal use of them.“ For example, the governments of Algeria, Egypt, and Mozambique, all countries with abundant natural gas, have by and large failed to tap into this resource to power the region’s economies and more specifically to turn it into fertilizer and ultimately more food. Only a tiny fraction of the natural gas produced and imported to the region is combined with nitrogen from the air to make ammonia, the foundation of nitrogen fertilizer. While African farmers used 4 million tons of urea to replenish their soils with nitrogen in 2017, they could in fact use two to three times that, according to the International Fertilizer Development Center. But these farmers are unlikely to get the chance because on the current trajectory, they will see 2-3% more urea every year until in 2035, according to Nexant’s projections.

Among the many causes for this low average growth rate are businesses that seeking to invest in natural gas production, or in factories to convert that gas to soil amendments, being put off by political instability, corruption, and the challenge of finding reliable distributors and consumers; farmers, many of whom are smallholders, lacking access to fertilizers or the funds to buy them; then there is the ensuing low crop productivity, high prevalence of hunger, and the destruction of natural habitats to increase cropland; and last but not the least water resource issues and climate change. Signatories to the Abuja Declaration have committed to make strides against these forces, but they face many challenges. These challenges are felt less keenly in Egypt and South Africa, for instance, where per-hectare urea application rates approach those in developed countries.